The perfect storm called artificial intelligence and geospatial big data

On April 20, 2010, when BP’s deep-water drilling rig Deepwater Horizon exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, the oil giant claimed that the spill was just 1,000 barrels per day. A small non-profit in West Virginia, SkyTruth, studied the satellite observations of the oil slick, cataloged its computations, and concluded that the spill was at least 20 times bigger than what was being claimed. The report was quickly picked up by the media, and lead the US government to straightaway increase the estimate to 5,000 barrels of oil per day.

The same year, UBS Investment Research had two teams quietly working on Wal-Mart’s quarterly earnings preview – one using time-honored traditional methods, the other studying the satellite pictures of the American retail brand’s parking lots to gauge the customer footfall. Each came up with a different revenue forecast. No prizes for guessing which team’s projections were more accurate.

The same year, UBS Investment Research had two teams quietly working on Wal-Mart’s quarterly earnings preview – one using time-honored traditional methods, the other studying the satellite pictures of the American retail brand’s parking lots to gauge the customer footfall. Each came up with a different revenue forecast. No prizes for guessing which team’s projections were more accurate.

When these analytical use cases for commercial satellite imagery made headlines, the space economy had only begun to detangle itself from the clutches of governmental monopoly. Today, plummeting launch costs and the deluge of small and affordable satellites have guaranteed that we have many more eyes in the skies – revisiting different parts of the earth at a much greater frequency, and taking our cache of high-definition EO imagery beyond the scope of human analysts.

Thankfully, this invasion of big data has been accompanied by an equally vigorous advancement in data analysis techniques (like classification and prediction) which have been the driving force behind geographic information systems (GIS). Technologies like artificial intelligence, deep learning and machine learning have matured just in time to equip us with the tools we need to make sense of an ever-increasing trove of imagery data. (Read: What’s the difference between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Deep Learning?)

So, when Facebook wants to find out the exact geographical locations where people do not have access to the Internet, all it needs to do is take 350 TB of satellite imagery and run it through an AI-enhanced image-recognition engine. After processing 14.6 billion pictures, the company can identify more than 2 billion disconnected people across 20 countries.

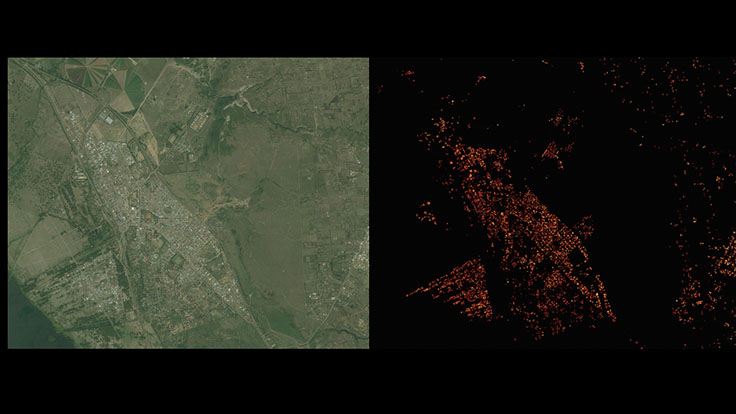

Satellite imagery of Naivasha, Kenya (left) and Facebook’s analysis of the same (right)

Researchers at Stanford University adopt a similar approach while making predictions on poverty. They ask a machine learning system to compare daytime and nighttime satellite imagery and see which areas are devoid of artificial lights – a tell-tale sign of lack of affluence.

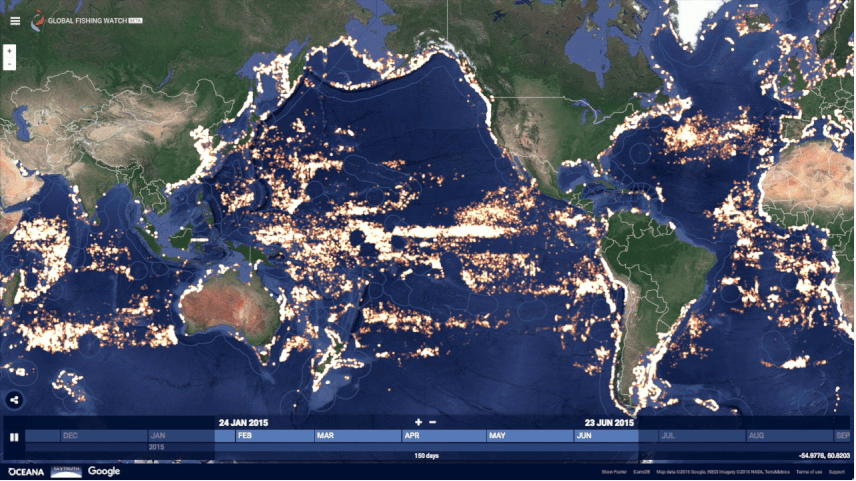

The same technology enables Global Fishing Watch’s tracking platform to comb through 22 million location logs provided by ocean vessels every day and determine what kind of fishing gear is being used by what kind of ship – allowing citizens, governments and researchers across the planet to access data about commercial fishing activity in a manner that simply didn’t exist earlier.

Global Fishing Watch

Among the things that didn’t exist earlier also fall geospatial data refineries. Today, we have highly-specialized startups whose only job is to dig through the wealth of imagery data captured by companies like Airbus, DigitalGlobe, and Planet, and extract extraordinary insights from them.

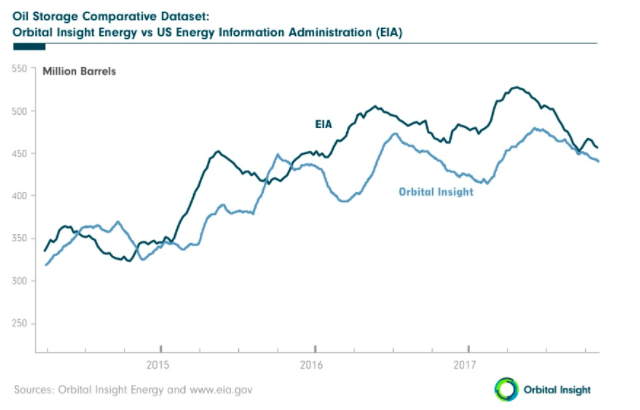

Take Orbital Insight for example. This geo-analytics startup is working to help stabilize the price of oil by giving investors an unprecedented look into the volume stored by countries whose public data cannot be readily trusted. At the end of 2014, by analyzing high-res sat imagery for aboveground oil storage, Orbital Insight was able to identify 2,100 petroleum reserve tanks in China – four times more oil than what was being reported by the industry’s standard database.

In another project, the company sifted through daytime satellite imagery for the World Bank, zeroing down on geospatial features like buildings in developed areas, car density, and agricultural land. These features would go on to serve as useful indicators of economic activity and poverty at the local level and help the World Bank determine where it should focus its efforts more.

Another geo-analytics startup, Descartes Labs, is looking at tons of pixels generated by satellites to predict food yields months in advance of current standards. The company collects data from every single farm in the United States on a daily basis and uses spectral information to measure chlorophyll levels in crops. In essence, Descartes Labs is working to help alleviate a food crisis even before it happens!

SpaceKnow, meanwhile, is monitoring over 6,000 industrial facilities across China by comparing satellite imagery and assigning values for optical changes like visible inventory or a new building. This allows the startup to make independent predictions about China’s economy in its China Satellite Manufacturing Index, which even went live on Bloomberg Terminal last year.

SpaceKnow is monitoring over 6,000 industrial facilities across China

These are only a few instances where the coalescing of remotely-sensed data with computer vision, machine learning, and artificial intelligence has aided investments funds, Fortune 500 companies, humanitarian organizations, et al, to observe global socio-economic trends – and keep an eye on the planet as if it were a living entity – at the speed of business.

As the analytics metamorphoses from conjectures to precision, the implications for multi-billion industries can be pretty incredible. And geospatial companies are only beginning to explore the tip of this big data analytics iceberg.